Timelines Through a Fish Eye Lens: Fish Quilt

Dimensions: 54” x 39”

Materials: Quilt patch squares - salvaged and repurposed fabrics of cotton and silk from sheets, pants, jeans, skirts, and other remnants sourced from Carolyn Hall and David Figueroa; Quilt binding and backing cotton fabrics sourced from David Figueroa; Quilt batting donated by Athena Kokoronis; Cotton and polyester thread; Fabric pen and sharpie pen inks; Stamp ink.

I have centuries of data on the history of fish species and the fisheries in New York City waters. I’ve been researching this industry for years and the stories embedded in the data are many, complex, and show patterns of use and abuse, loss and resilience. It’s an overwhelming amount of information that I’ve shared in bits and pieces, but I’ve never released it all to the public. A book seems daunting, an academic paper isn’t enough and doesn’t reach most of the people in New York City that I would like to. As a dancer, I also wanted to make it physical, tangible, spatial, and interactive.

I first wrote out my historical data in timelines on dot-matrix printer paper while in a residency with the Domestic Performance Agency. There were six timelines, and they wrapped around the room. The starting point or center was a timeline specifically about the fish species found in the waters around New York City and the fisheries based on them. I recorded any piece of qualitative or quantitative research, fact or anecdote, that I found referring to fish or how humans saw or used them from the formation of the New York Bay to the near-present. And since fish lives and watery homes are important natural resources that humans have altered since we learned how to catch them, their history is intimately affected by our socio-political and cultural developments. I also wrote out timelines following our New York City history with politics, human population, pollution, technology, and climate.

The timelines satisfied me in that they took up space. They were touchable. People could enter the room and read as little or as much of my handwritten data as they wanted. They had the sensory impact of a stretch of time by the length of the papers and the accumulation of decades or the connections that could be seen in one year between a fish species, the number and types of humans living in New York, the weather events, what fish were on menus, and the recorded pollution.

But the timelines were still an overwhelming amount of information.

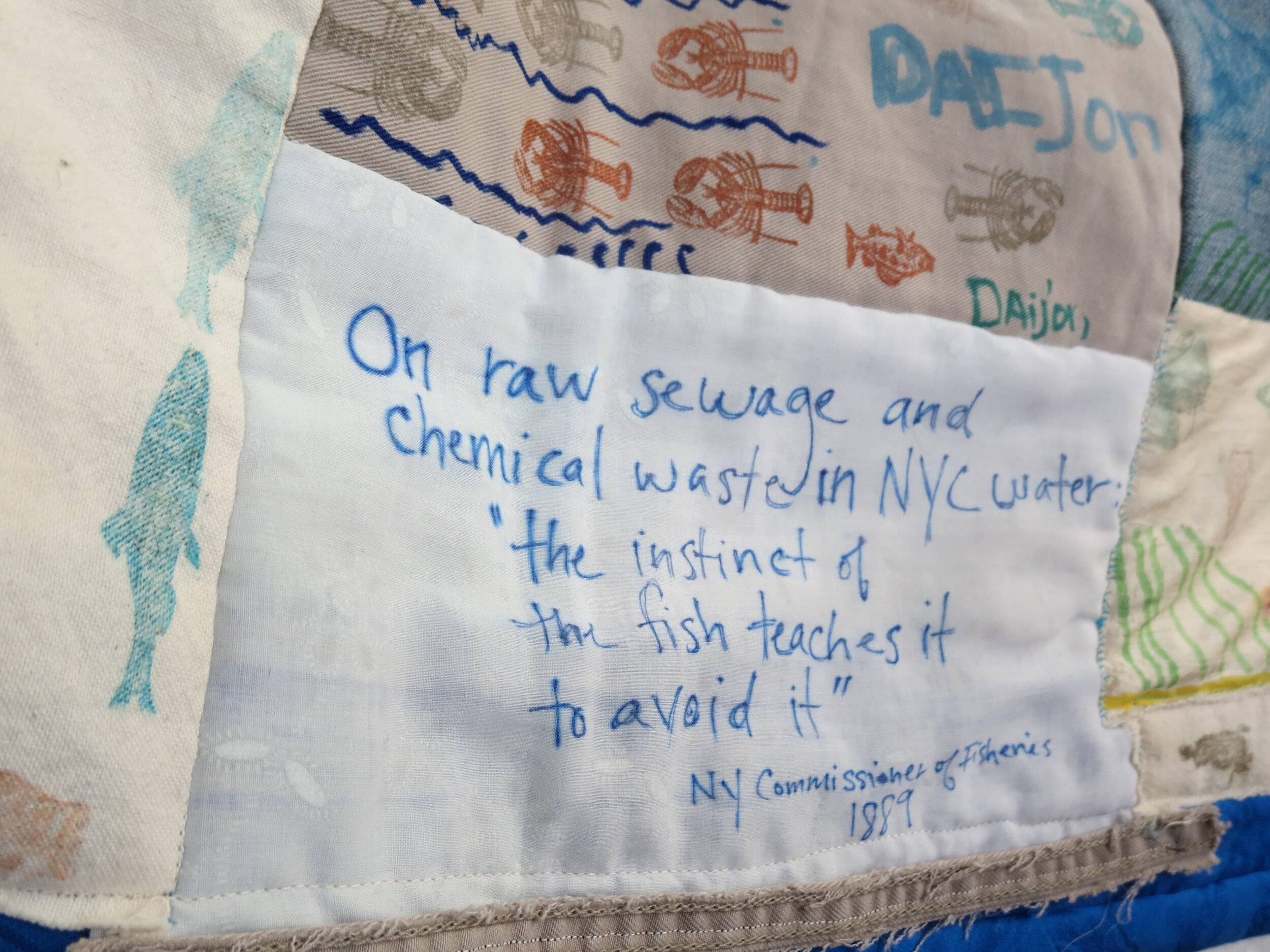

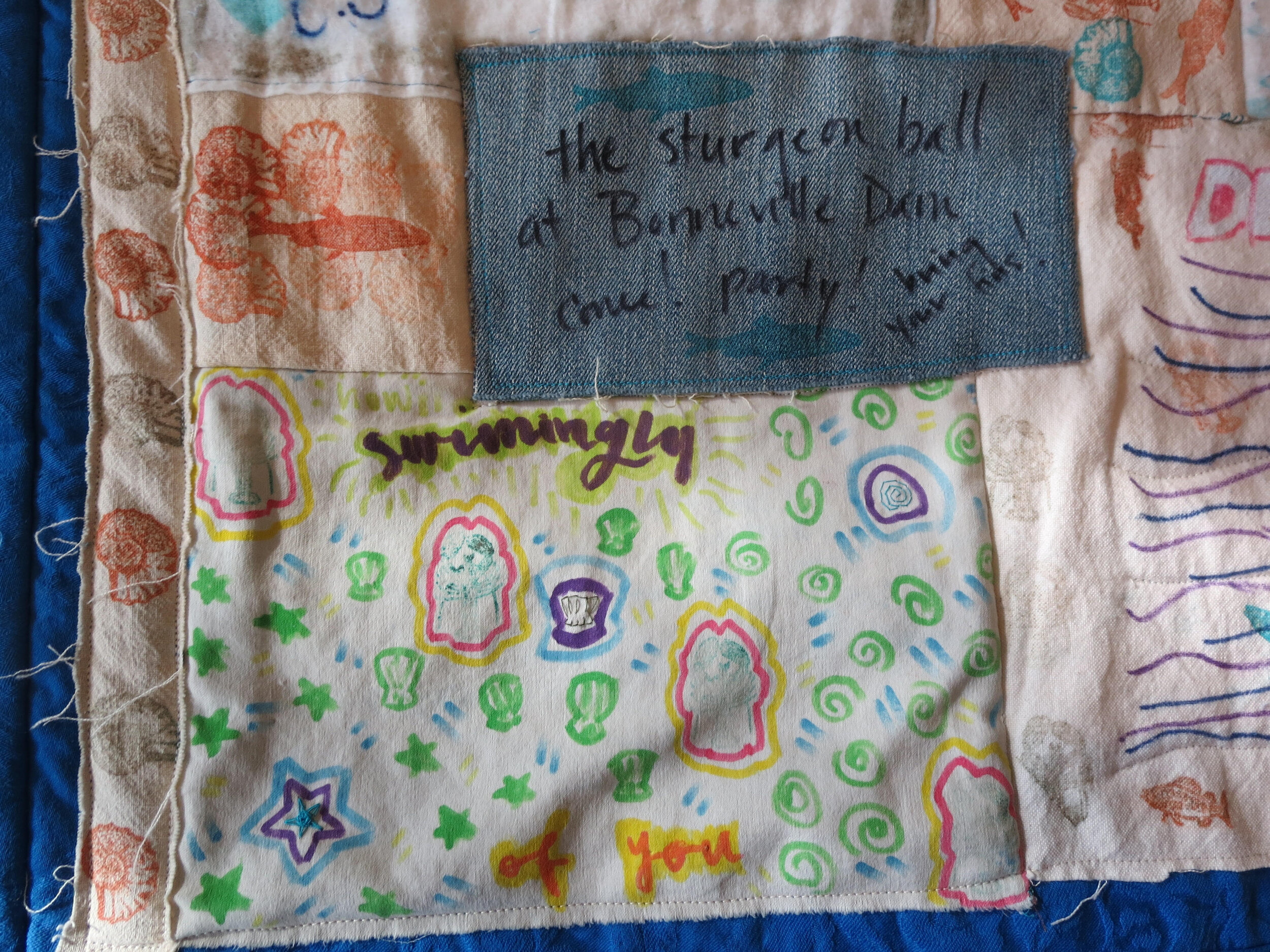

During the residency on Governors Island, I put up the timelines again and continued to work with them, but I also wanted to hear how the public related to the fish and water of New York City. I wanted to engage them creatively and physically. I brought in scraps of material, pens, stamps, menus, historical illustrations of local fish, and while some of my visitors read the timelines, others drew and stamped pictures or wrote about fish in their own words. I decided to make a fish quilt to stitch together images of their stories and mine.

Some of the panels are quotes from my research or diagrams that depict a story in the data. But most of them are drawings or quotes by people who came through my room, looked at the timelines on the wall, and talked to me. Nothing like having stamps and pens and scraps of material to keep hands busy and creative while talking about fish and the New York Harbor. When I was starting to stitch pieces together, I had one girl sit and embroider sea stars and shells with me for an hour. She had just learned embroidery and wanted to practice. Her mom stayed and her brother and dad wandered about the island. Whole families contributed from young kids to grandparents. We had a great time drawing, talking, stitching, and bonding over art and fish. It was personal and intimate. I definitely reached a cross-section of New York City residents and visitors I wouldn’t have by writing a paper.

It’s my first quilt. It was satisfying to puzzle it together, to see how the stories sat side by side, and to stitch those last stitches. It is flawed, it is rough, it is contradictory, it is full of life and thought and hope and loss, and it is beautiful—much like the history, the fish, and the people it represents.

About the Artist

Carolyn Hall is a Brooklyn-based historical marine ecologist, dancer/performer, and science communications instructor. She works freelance at all of these and is currently involved with Third Rail Projects, Carrie Ahern Dance, the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, the American Fisheries Society, and Works on Water. In collaboration with Clarinda Mac Low, she creates and leads Sunk Shore, an experiential site-specific shoreline walk that addresses climate change by envisioning a speculative future. She is increasingly invested in combining her artist and scientist halves to make data-rich science more understandable, embodied, and memorable for the general public.